Mary Barnes Langford, the daughter of William Barnes and Sarah Sims, was very glad indeed of her sisters, and her cousins, and her aunts surrounding her in the village, as she would otherwise have felt very lonely indeed.

Mary Barnes Langford, the daughter of William Barnes and Sarah Sims, was very glad indeed of her sisters, and her cousins, and her aunts surrounding her in the village, as she would otherwise have felt very lonely indeed.

She had just seen her husband, Thomas, off to war. They had been married seven years, and had two daughters, Lillian and Dorothy, who were now five and three years old. They couldn’t understand what had happened to their father, but they were bewildered and seemed to spend a lot of time squabbling with each other. She realised that this was probably partly because of her own mood, which was anxious and sad. Sad of course because she missed her husband, but anxious because she could not see how they were going to make ends meet.

Thank goodness for her mother, who had lived with them ever since they came to Ivy Cottages. At 79 years old, she was not really up to looking after the girls single-handed if she could find work, but that might be what was needed. Perhaps she could find work she could do at home, taking in people’s laundry or something.

Thank goodness for her mother, who had lived with them ever since they came to Ivy Cottages. At 79 years old, she was not really up to looking after the girls single-handed if she could find work, but that might be what was needed. Perhaps she could find work she could do at home, taking in people’s laundry or something.

Mary was in that annoying state where she couldn’t quite manage to cry, but couldn’t quite pull herself together either.

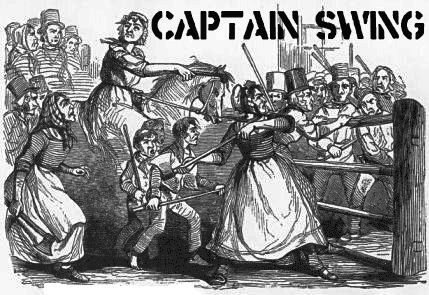

‘Remember you are a Sims!’, she said to herself, in an attempt to reach deep within to draw on her famous family toughness. Why, her great-uncle Daniel Sims* was the St Mary Bourne equivalent of the Tolpuddle Martyrs!

Great Uncle Daniel had been a worthy follower of Captain Swing

When 19th c. politicians and pamphleteers spoke of the English ‘peasants’, they did not mean direct family cultivators, but agricultural wage-labourers. In fact the English agricultural population divided into three – at the top stood a small number of landlords, who between them owned most of the land. The first attempt to discover how the land of Britain was owned (in 1871-3) revealed that about 1200 people owned ¼ of the UK, and about 7,200 owned ½ though it certainly underestimated the concentration of landed property…

This comparative handful of giant landlords rarely cultivated their estates themselves…they rented them out to tenant farmers who actually exploited them. In 1851, when the first nationally reliable figures were collected, there were about 225,000 farms in Britain, about ½ of the 100-300 acres in size and all of them averaging just over 110 acres, ie what passed for a small farm in England would certainly have counted as a giant farm beside the smallholdings of typical peasant economies. Just over 300,000 described themselves as farmers and graziers, who cultivated their farms b y employing the 1.5 million men and women who described themselves as agricultural labourers, shepherds, farm servants etc, ie the typical English agriculturalist was a hired man, a rural proletarian…

Of course rural society consisted not only of those actually engaged in land ownership or farming, but also of the numerous craftsmen, shopkeepers, carters, innkeepers etc who provided the services necessary to agriculture and village life…

It was in Hampshire and Wiltshire that the movement, as it drove westwards, became the most widely dispersed and attained its greatest momentum. When the riots were all over, there were 300 or more prisoners awaiting trial in each county, compared with a little over 160 in Berkshire and Buckinghamshire and a little over 100 in Kent. Yet in both [counties] the riots were remarkably short-lived.

[As reported in The Times of 27-29 November 1830], Hampshire, Berkshire and Wiltshire were chiefly concerned with machine breaking [whereas the other counties were chiefly fire-raising]. In Wiltshire, it was said of the small farmers that, even if they did not actually take part in the riots, they are ‘glad to see the labourers at work’ and many farmers were half-hearted in the defence of their machines and made the labourers’ task an easier one. Their hostility to tithe and rent was deeper and led them, on occasion, to become active accomplices.

18 November 1830 St Mary Bourne Arson attack on large farmer – ricks were fired, setting off riots in the area 21 November 1830 Vernham Dean A ‘robbery’, ie acquiring money or food by menace 21 November 1830 Hippenscombe Threshing machine destroyed 22 November 1830 Ashmansworth Villagers compelled their rector to pay them 2/- 22 November 1830 Hurstbourne Tarrant ‘Robbery’ to the value of £1 22 November 1830 Vernham Dean ‘Robbery’

Between 18th and 24th November 1830, there were incidents in Andover, Barton Stacey, Broughton, Bucklebury, Buttermere, East Woodhay, Great Bedwyn, Ham, Highclere, Hippenscombe, Houghton, Hungerford, Inkpen, Kintbury, Lambourn, Leckford, Ludgershall, Mottisfont, Overton, Stockbridge, the Wallops and Upper Clatford.[i]

Thomas is believed to have been part of the Territorials called Hampshire Fortress:

The following is a list of units transferred to the Territorial Forceon 1 April 1908, or raised in that year under the terms of the Territorial and Reserve Forces Act 1907, and the associations by which they were administered.[1] … A number of units, particularly those attached to the Royal Garrison Artillery and Royal Engineers, had their titles altered again in 1910.[2]

Hampshire (Fortress) Royal Engineers (Nos. 1, 2 and 3 Works Companies, Nos. 4, 5 and 6 Electric Light Companies)

*Daniel Sims is on the tree – and marked with a small green leaf in the corner. His transportation to Australia with his “co-conspirators” is covered in Julie Muirhead’s blog post here.

[i] Captain Swing by E J Hobsbawm and George Rudé, Lawrence and Wishart 1969